A London 2012 highlight is the men's 100m sprint final – and it's much more than sport to Jamaicans, who have high Olympic expectations for Bolt and Yohan Blake

Hugh Muir

guardian.co.uk

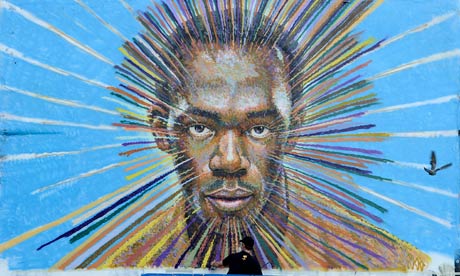

Usain Bolt is the subject of a mural in east London by street artist James Cochran, also known as Jimmy C, to celebrate the Olympics. Photograph: Paul Hackett/Reuters

It's relaxed by design at Jamaica House, the Jamaican Olympic home from home at London's North Greenwich Arena. There are comfy chairs in the dimly lit bar; bed-sized cushion seats around the terrace. The reggae is melodic, the old style.

But it would be a mistake to think that any of those feasting on jerk pork and rum cocktails view the men's 100m sprint final with anything but a steely focus. This is sport, but it is so much more than that.

Jamaica already has the 2012 Olympic women's 100m gold medallist in Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce; but that's just the start. The quest for a nation of just 2.9 million people to be recognised as unassailable – if only on the 100m track – is deadly serious. And in this week of all weeks; the 50th anniversary of Jamaican independence.

"If you look at the way the world is, America tries to dominate at everything," says London-based Jamaican Clive Daley. "And normally they are able to do that. But this is one thing dominated by Jamaica – not just Usain Bolt, also the others. Might is not always right. It is a signal that the weaker nations can punch their weight."

A fillip for black Britain too, he says. "There is a lot of psychological pressure on people. Some people feel lesser. But you don't have to feel that way when there is something like this you can embrace."

Miriam Williams, a singer-songwriter from Hackney, agrees: "This is more than sport in terms of the esteem it gives all of African origin. It's a big thing."

Richie Bailey, a London bike courier, soaks up the atmosphere and gives his verdict to reporters. "My man Bolt is gonna beat them bad, man," says Bailey. "This weekend, Jamaica is gonna be the most powerful nation on earth."

They all think their champion will win big, but if it is not him, they expect the victor to be his compatriot Yohan Blake. They expect Jamaica to take places one and two. And if that happens, the timing will be exemplary.

These are difficult days for the proud people of the largest West Indian island, amid political turbulence and the continuing effort to find a place for itself in the global markets of the 21st century. Like so many of the islands, it leans heavily on tourism. Last year, 3 million visited, an increase of more than 8% on the previous year and an all-time record.

But success on that scale is needed because the other side of the ledger flags up the difficulty Jamaica has making its mark in the world. Its main exports are bauxite, of which it has the second largest supply in the world, sugar, bananas, coffee, drinks, tobacco and chemicals. But world demand for sugar has dropped alarmingly and bananas lose out to imports from South America. In 2011, compared with 2010, the country's trade deficit ballooned by 30%.

"Things we once excelled at in terms of trade have become more difficult," reflects Craig Linton, of Hanover, north-west Jamaica, standing by the terrace bar. "Anything we can do to get ourselves out there is critical. That's why we rally around someone doing so well."

They crave a Bolt effect in Jamaica. Could there be a Bolt bounce here too? There could be; for these are also difficult times for communities of West Indian origin in Britain. More than half of the young black men available for work are unemployed and they are more like to end up in prison than in a top university. As the recession bites, low-paid minority workers fear for their jobs.

Against this backdrop, what is there to keep heads high? In a political context there was the election of President Obama. For the Windrush generation and the generation after, there was the West Indies cricket team; all-conquering sportsmen who well appreciated the wider impact of their success on West Indians here and on the islands. But what since?

Maybe Usain Bolt. But British academic and broadcaster Robert Beckford says Bolt's success has so far resulted in contradiction. "On the one hand, he represents the best Jamaica can do in terms of using natural talent married with hard work and discipline and focus to be the best in the world. On the other hand he represents the failure of post-slavery societies to develop their economic base and their cultural reach beyond sports to make this kind of achievement less important."

In Britain, says Beckford, there is some feeling of pride about Bolt and his supremacy, but it is distant. Until last night, at least Bolt could be considered the best on the planet; but black Britons have other black Britons to cheer for. And the morale boost from sport has its limits. "Behind it lies the harsh reality that most black men of Usain Bolt's age are likely to be unemployed or under-employed, or have a criminal record."

Henry Bonsu, director of the black digital radio station Colourful, agrees. "People will be happy if he wins. But when it all dies down, the world will still be as it is, and they will still be left trying to make things better then they were."

Can Bolt – an athlete – do anything to change that? Should he be expected to try? Yes, says fan Craig Linton. "I know he does a lot in his home village, but as to speaking about other things, I haven't heard that from him. I hope he will recognise the opportunity and use it to do as much as he can."

Bonsu, however, thinks the sportsman will stick to sport. "We don't expect to hear any pearls of wisdom from him."

The truth is that no one knows what happens next. It could be another rewriting of the history books by the fastest man on the planet. It could be the ascent of a rival, perhaps Blake, and the dethroning of the king. It could be a shock reversal from the Americans. At Jamaica House they sip rum cocktails and wait.

Hugh Muir

guardian.co.uk

Usain Bolt is the subject of a mural in east London by street artist James Cochran, also known as Jimmy C, to celebrate the Olympics. Photograph: Paul Hackett/Reuters

It's relaxed by design at Jamaica House, the Jamaican Olympic home from home at London's North Greenwich Arena. There are comfy chairs in the dimly lit bar; bed-sized cushion seats around the terrace. The reggae is melodic, the old style.

But it would be a mistake to think that any of those feasting on jerk pork and rum cocktails view the men's 100m sprint final with anything but a steely focus. This is sport, but it is so much more than that.

Jamaica already has the 2012 Olympic women's 100m gold medallist in Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce; but that's just the start. The quest for a nation of just 2.9 million people to be recognised as unassailable – if only on the 100m track – is deadly serious. And in this week of all weeks; the 50th anniversary of Jamaican independence.

"If you look at the way the world is, America tries to dominate at everything," says London-based Jamaican Clive Daley. "And normally they are able to do that. But this is one thing dominated by Jamaica – not just Usain Bolt, also the others. Might is not always right. It is a signal that the weaker nations can punch their weight."

A fillip for black Britain too, he says. "There is a lot of psychological pressure on people. Some people feel lesser. But you don't have to feel that way when there is something like this you can embrace."

Miriam Williams, a singer-songwriter from Hackney, agrees: "This is more than sport in terms of the esteem it gives all of African origin. It's a big thing."

Richie Bailey, a London bike courier, soaks up the atmosphere and gives his verdict to reporters. "My man Bolt is gonna beat them bad, man," says Bailey. "This weekend, Jamaica is gonna be the most powerful nation on earth."

They all think their champion will win big, but if it is not him, they expect the victor to be his compatriot Yohan Blake. They expect Jamaica to take places one and two. And if that happens, the timing will be exemplary.

These are difficult days for the proud people of the largest West Indian island, amid political turbulence and the continuing effort to find a place for itself in the global markets of the 21st century. Like so many of the islands, it leans heavily on tourism. Last year, 3 million visited, an increase of more than 8% on the previous year and an all-time record.

But success on that scale is needed because the other side of the ledger flags up the difficulty Jamaica has making its mark in the world. Its main exports are bauxite, of which it has the second largest supply in the world, sugar, bananas, coffee, drinks, tobacco and chemicals. But world demand for sugar has dropped alarmingly and bananas lose out to imports from South America. In 2011, compared with 2010, the country's trade deficit ballooned by 30%.

"Things we once excelled at in terms of trade have become more difficult," reflects Craig Linton, of Hanover, north-west Jamaica, standing by the terrace bar. "Anything we can do to get ourselves out there is critical. That's why we rally around someone doing so well."

They crave a Bolt effect in Jamaica. Could there be a Bolt bounce here too? There could be; for these are also difficult times for communities of West Indian origin in Britain. More than half of the young black men available for work are unemployed and they are more like to end up in prison than in a top university. As the recession bites, low-paid minority workers fear for their jobs.

Against this backdrop, what is there to keep heads high? In a political context there was the election of President Obama. For the Windrush generation and the generation after, there was the West Indies cricket team; all-conquering sportsmen who well appreciated the wider impact of their success on West Indians here and on the islands. But what since?

Maybe Usain Bolt. But British academic and broadcaster Robert Beckford says Bolt's success has so far resulted in contradiction. "On the one hand, he represents the best Jamaica can do in terms of using natural talent married with hard work and discipline and focus to be the best in the world. On the other hand he represents the failure of post-slavery societies to develop their economic base and their cultural reach beyond sports to make this kind of achievement less important."

In Britain, says Beckford, there is some feeling of pride about Bolt and his supremacy, but it is distant. Until last night, at least Bolt could be considered the best on the planet; but black Britons have other black Britons to cheer for. And the morale boost from sport has its limits. "Behind it lies the harsh reality that most black men of Usain Bolt's age are likely to be unemployed or under-employed, or have a criminal record."

Henry Bonsu, director of the black digital radio station Colourful, agrees. "People will be happy if he wins. But when it all dies down, the world will still be as it is, and they will still be left trying to make things better then they were."

Can Bolt – an athlete – do anything to change that? Should he be expected to try? Yes, says fan Craig Linton. "I know he does a lot in his home village, but as to speaking about other things, I haven't heard that from him. I hope he will recognise the opportunity and use it to do as much as he can."

Bonsu, however, thinks the sportsman will stick to sport. "We don't expect to hear any pearls of wisdom from him."

The truth is that no one knows what happens next. It could be another rewriting of the history books by the fastest man on the planet. It could be the ascent of a rival, perhaps Blake, and the dethroning of the king. It could be a shock reversal from the Americans. At Jamaica House they sip rum cocktails and wait.

No comments:

Post a Comment